Education and AI: The Global South Steps into the Heart of the Global Debate

Hicham TOUATI

Gathered in Fes, experts and decision-makers from several continents convened—under the impetus of the Tamkine Foundation and with the support of the Euro-Mediterranean University (Euromed)—for a pre-summit affiliated with the India–AI Impact Summit 2026. The objective: to shift artificial intelligence from a source of division to an educational “dividend,” by placing equity, governance, and teacher training at the center of the debate.

On Wednesday, January 21, 2026, at UEMF, one idea ran through the discussions like a common thread: transforming a global concern into a shared horizon. In the amphitheater—and beyond, thanks to a hybrid format—academics, experts, and national and international institutional stakeholders gathered around a single dilemma: can artificial intelligence be anything other than an accelerator of inequality in education? The Tamkine Foundation for Excellence and Creativity made this question the core of a high-level forum designed as a pre-summit ahead of the India–AI Impact Summit 2026, scheduled for February 19–20 in New Delhi.

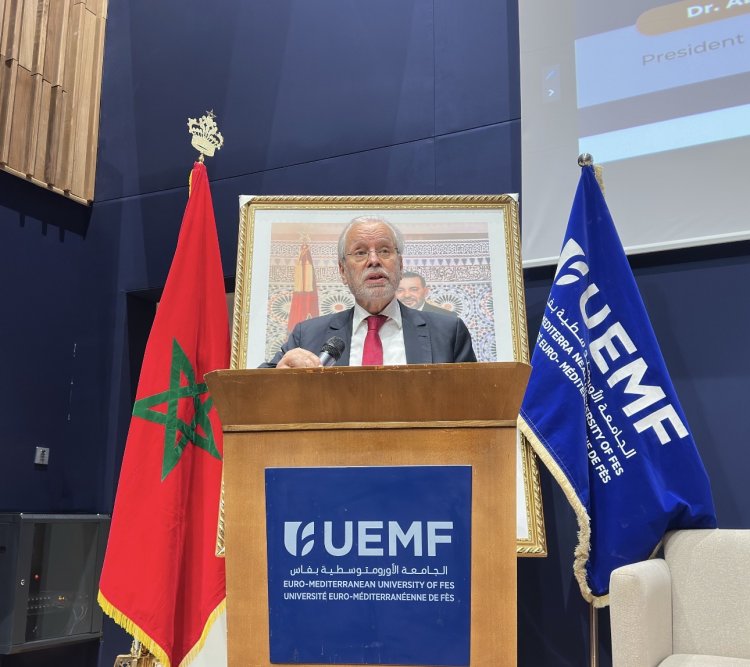

The choice of the Euro-Mediterranean University of Fes was far from incidental. It was intended as a statement in itself. “We are meeting at a pivotal moment when artificial intelligence is no longer a promise for the future, but a rapidly accelerating dynamic,” emphasized Abdelilah Kadili, President of the Tamkine Foundation, in his opening address. AI, he recalled, “is reshaping economies, redefining skills, and profoundly transforming the very architecture of knowledge,” yet its expansion is accompanied by “risks of fragmentation, exclusion, and imbalance.” The challenge is therefore clear: to ensure that AI becomes “a lever for shared progress, rather than a new driver of inequality.”

Held under the theme “From the AI Divide to the AI Dividend: a Roadmap Driven by the Global South to Democratize Artificial Intelligence in Education,” the meeting addressed very concrete issues: leadership, policy coherence, trustworthy governance, infrastructure, teacher empowerment, and large-scale human capital development. In other words: how to prevent schools from becoming a technological mirror of global imbalances, where some students learn faster simply because they are better equipped, better connected, better trained, and better supported.

This pre-summit was not intended as a mere exercise in rhetoric. “We did not organize this pre-summit to add yet another event to an already saturated international agenda,” Mr. Kadili insisted. “Today, being informed is no longer enough (…) We must contribute, build, and add our stone to the collective edifice.” Behind the words lies a clear idea: the Global South no longer wishes to be a testing ground for solutions designed elsewhere, but rather a space for proposal, experimentation, and direction-setting.

As a partner of the event, the Euro-Mediterranean University of Fes played both an institutional and symbolic relay role. In a context where technological innovation is often narrated from Northern capitals, hosting this debate at a Moroccan university redraws the geography of the discussion. “The choice of a university setting to host this dialogue is far from trivial; on the contrary, it is highly symbolic,” Mr. Kadili noted, thanking Euromed for its “hospitality and partnership,” which “made this moment possible.” The hybrid format further extended the room beyond its walls, in keeping with the spirit of inclusion being advocated: circulating ideas, engaging voices far from traditional centers of decision-making, and giving substance to an ambition often proclaimed but rarely organized.

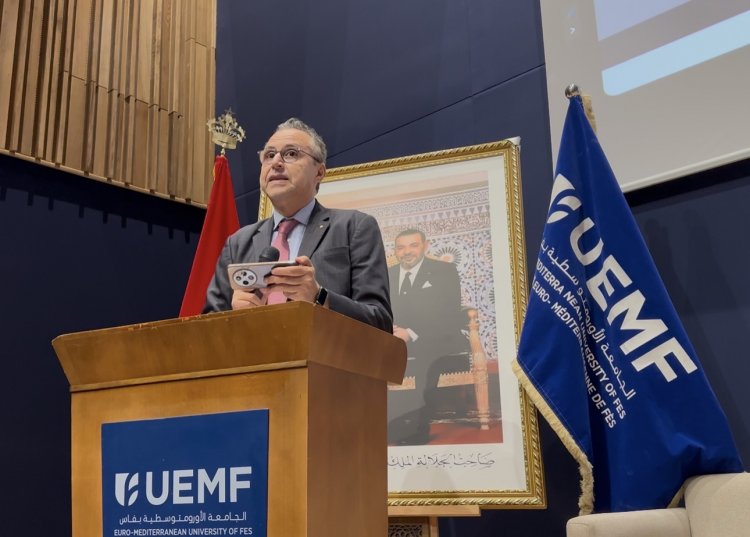

Among the speakers, one voice carried particular weight: that of Rachid Belmokhtar, Honorary President of the Tamkine Foundation and former Minister of National Education. In response to concerns surrounding AI—particularly regarding employment and the risk of “replacing humans”—he urged a shift in perspective: “It should be noted that AI can be a source of change and can serve two essential objectives, namely improving quality and equity.” For him, the immediate value of the pre-summit lay in bringing together in Fes academics and experts from Morocco, Mexico, the United States, Singapore, India, China, and Hong Kong, to generate ideas “that could contribute to the promotion of AI in education.”

The impact of the meeting is also measured by what it seeks to leave behind. Mr. Belmokhtar proposed the creation of an informal think tank, a “Fes Group,” dedicated to further exploring issues related to education and AI. The idea resonates as a natural extension of a country “in the midst of educational reform,” where integrating new data appears less as a choice than as a condition of sovereignty. “While AI disrupts certain concepts, it brings new pedagogical approaches that must be leveraged,” he added, outlining a vision of a school system that does not merely endure technology, but places it at the service of its own priorities.

This openness does not preclude vigilance. Abdelilah Kadili stressed “the imperative of avoiding pitfalls, risks, and problems inherent in the irresponsible and unethical use” of artificial intelligence in schools. He called for “pooling the actions of experts and academics” in order to move from a risk-centered approach to AI conceived as a “transformative resource for education.” This statement encapsulates the delicate balance sought in Fes: encouraging innovation without accepting opacity, accelerating without abandoning ethics, modernizing without widening the gap.

The pre-summit also fits into a trajectory that the Tamkine Foundation has been pursuing for more than a decade: education reform, digital transformation, and human capital development. It also extends a political and intellectual advocacy effort: the call for an “African Decade of Education,” grounded in the conviction that Africa must “actively shape global technological transformations” rather than adapt to them after the fact. In his address, Mr. Kadili summarized this intention unequivocally: “This pre-summit (…) affirms that the voice, experience, and aspirations of the African continent fully belong in the global debate on artificial intelligence and education.”

In Fes, the day also took the form of a bridge between intellectual heritage and technological acceleration. Academic Abdesamad El Fatemi presented his book The Dawn of Global Artificial Intelligence: Training Pathways and Arab Challenges, written in Arabic and English. The work aims to popularize AI for a broad audience while recalling—through the history of science and mathematics—the contributions of figures such as Al-Khwarizmi, Ibn Sina, and Ibn al-Haytham. “The Arab world must become aware of its historical contribution to the development of science,” he argued, calling attention to the “frenetic race” toward AI development and the choices Morocco must make to assume regional and continental leadership.

Within the very architecture of the India–AI Impact Summit 2026, these pre-summits held around the world are designed to produce well-grounded regional contributions and concrete proposals to inform deliberations in New Delhi. Fes therefore aims to carry weight not through the volume of declarations, but through the precision of its orientations. Abdelilah Kadili summed this up as an invitation to collective responsibility: to participate “not as mere observers, but as co-authors of a shared reflection,” because the value of such a meeting “will not be measured by the elegance of speeches, but by the clarity of the orientations identified and the strength of the ties” it helps to forge.

At the end of the day, one question remains—one that extends beyond the walls of an amphitheater: will AI in education be a luxury reserved for the most privileged, or a tool for educational justice? In Fes, the Tamkine Foundation and Euromed University sought to set a direction: to make the Global South not a peripheral actor in the debate, but one of its centers of gravity. What comes next will depend on the ability to turn proposals into policies, principles into infrastructure, and promises into classroom practices—where, ultimately, the technological future takes its most concrete form: in the hands of a teacher and the gaze of a student.